Copyright © 2017 Setzer Law Firm

A Man Goes Mad

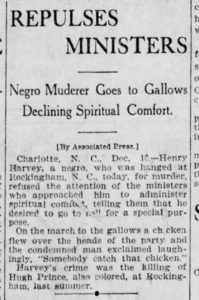

A murder conviction sent Henry Harvey to the gallows. That’s most of what we know about his life, because he wasn’t the sort of man anyone cared much about back then. In fact, if he hadn’t been hanged, he would have been forgotten long before now.

Harvey came to the fast-growing Sandhills town of Rockingham, North Carolina, from Roanoke, Virginia. He was part of a crew hired to help with the construction of the town’s waterworks and sewer service. Rockingham was moving into the modern age of indoor plumbing. It was 1908, after all. And Harvey was part of the team hired to make it happen.

Digging ditches by hand in the burning heat of a Southern summer wasn’t a glamorous job. Laying sewer pipe was even less glamorous. But it paid cash money, and if Rockingham was to have running water and flushing toilets, someone had to do the grunt work.

And as Henry Harvey toiled under the summer sun, he began to act strangely. A madness seemed to awaken inside of him. Maybe it was the heat in which he sweated, or maybe the hard liquor he drank, but he began to act peculiar as the backbreaking work wore on.

By mid-July, Harvey began “dissipating” people said, and it continued “for several days.” Then, one Friday afternoon, Harvey’s boss described him as “unusually nervous.” That was the last day of hard labor he would ever perform.

The next morning, Harvey had lost most of his appetite. Still, he managed to choke down a little soup for lunch. He also found a way to binge on liquor.

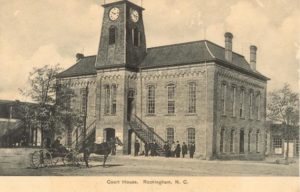

As nighttime approached, Harvey and his roommates, Gilmore Dickenson and Hugh Price, began a game of craps. The three friends shared a run-down shanty together just inside the long shadow of the courthouse, and craps was as good a way as any to pass time. When Harvey lost, as drunken gamblers usually do, the instability inside of him welled up again. He began arguing with Dickenson. Price tried to play peacemaker between the men, only to find himself the new focus of Harvey’s crazed and drunken rage.

Then, as suddenly as the arguments began, they ended. Harvey’s threats of violence stopped and things settled down. Afterwards, all three men slept on the porch of the shanty, where a slight overnight breeze made the miserable heat of the sweltering July night just a little more bearable. Had he wanted to, Harvey could have risen up and killed either of his shanty roommates in the darkness that night, but he didn’t.

Instead, Harvey slept peacefully. He woke the next morning, Sunday, July 19, calm and rational, and wandered off to a neighboring shanty. A woman inside offered to cook breakfast for Harvey and his shanty mates, and his appetite had improved. He rounded up his friends and sent them over to eat. Before heading back over himself, though, he took a large drink of liquor. That was his mistake: Liquor stirred his internal demons, and, once awaked, they exploded with a passion.

By the time he returned for breakfast, Harvey was in tears. Suddenly, his temper flared and he slapped a child for no apparent reason. If anyone scolded him for the violence, that part of the story is lost. Harvey stood up from the table and strode out of the shanty with a purpose, leaving his friends to eat their morning meal in peace, or so they assumed. That peace wouldn’t last much longer.

Harvey soon reappeared, standing outside of the shanty and hollering that he intended to kill everyone inside. It was all the warning anyone would have. Harvey burst in, gun in hand, and began firing wildly. He hit Hugh Price first, with a shot that probably killed him. He turned to shoot Dickenson and their hostess, but both had fled from the breakfast table. Still, Harvey managed to put a bullet in Dickenson’s leg.

When he ran out of ammunition, Harvey left, reloaded, and returned to the shanty. Price was the only one still there, lying on the floor, blood pouring from his wounds. If Price wasn’t dead already, Harvey finished the work. He put several more bullets in Price’s head.

Inexplicably, the evil inside of Harvey seemed satisfied, at least for the moment. But that’s the way it worked on his mind, leaving him calm for time enough to lure people close, then turning him into explosive and dangerous man. Harvey put down his gun and went through the neighborhood singing hymns and looking for note paper on which to write a letter home. He showed no interest in trying to escape.

The law arrived quickly to arrest him, but Harvey was not quite ready to go. “I have only killed a man or two,” he told the officers, quite calmly. “I want to kill some more.”

Officers did not give Harvey the opportunity. They put him in prison, where he stretched out on the floor and vomited violently for quite some time.

The Conviction

At his mid-September trial, Harvey blamed poisonous liquor for the murder. That liquor, he said, made him crazy. Dr. N.C. Hunter and Dr. F.J. Garrett agreed. Harvey “could hardly be adjudged accountable, as knowing exactly what he was doing,” they said. Dr. L.D. McPhail went further still, testifying that Harvey was “temporarily insane.”

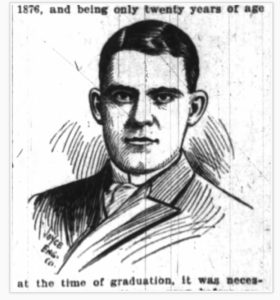

Attorney Settle Dockery represented Harvey. The prisoner could not have asked for a more talented lawyer. Dockery was “an unusually gifted young man of rare mental powers, a persuasive and magnetic speaker, a powerful and eloquent advocate before a jury,” the Raleigh News and Observer said. He was still in his early 30s, energetic and determined.

Dockery invested all of his massive talent in an effort to save Harvey’s life. Skilled as he was, Dockery could not win an acquittal. The jury found Harvey guilty, and Judge W.F. Long sentenced him to die.

So Harvey, who had declared, “I want to kill some more,” headed for the county gallows.

Harvey’s execution was scheduled for October 22, 1908. Attorney Dockery still refused to give up, and won one reprieve in October, then another in November. Meanwhile, influential citizens petitioned Governor Robert Glenn to review the case in detail, in a light most favorable to the murderer. Dockery added that he believed Harvey was of low intelligence, too weak-minded to understand what he was doing.

But Judge Long and Prosecutor L.D. Robinson insisted the man should hang. “The killing was barbarous in the extreme,” they said, “the only mitigating circumstance being that the prisoner had taken a drink of whiskey possibly containing poison.”

With his final chance to live resting in Governor Glenn’s hands, Harvey sat in prison and waited. Unfortunately, Governor Glenn was the last man Harvey wanted standing between himself and the gallows. Earlier in the year, Glenn cemented his reputation as the state’s “Prohibition Governor” by turning North Carolina dry. Ever after, he called the day he signed prohibition into law “the proudest day of my life.” Even under best circumstances, few had real pity for a man like Henry Harvey in 1908. Add in the fact Harvey was a weak-minded, drunken murderer, and he stood no chance with Governor Glenn. On December 16, the Governor upheld the ruling that Henry Harvey should hang.

To Hell for a Special Purpose

Richmond County Sheriff M L. Hinson had prepared for the inevitable. This would be the first and only execution he would oversee as Sheriff, but he had the gallows ready. In fact, the execution could not happen quickly enough for Sheriff Hinson. Henry Harvey was an unwelcome prisoner. Everyone watched uneasily as he sat in his lonely cell. With demons still hard at work on his mind, he “made many barbarous expressions with reference to death and eternity.” What he said, exactly, is lost to time. Apparently, the comments were too disturbing and profane for anyone to record.

Ministers came to meet with Harvey early on the morning of his execution, intending to to discuss heaven, forgiveness and Harvey’s eternal soul. Shockingly, Harvey refused to talk and sent them away. Sheriff Hinson was stunned. Prisoners bound for the gallows never refused the comforts of religion and the promise of an afterlife. No one but Henry Harvey, that is, because Harvey had no use for salvation.

A little after ten in the morning, Sheriff Hinson and Henry Harvey pushed through the large crowd towards the gallows, standing next to the courthouse on the town square. As he walked to his death, Harvey could see the new metal water tower he helped to construct, gleaming high above the buildings as a proud symbol of the town’s recent progress.

Normally, the ceremony from the scaffolding was a very solemn affair. Harvey’s however, was interrupted when a chicken took flight over the crowd. The man who showed no fear in the face of death suddenly broke into crazed laughter. “Somebody catch that chicken,” he said.

Public hangings, gristly as they were, drew a large crowd of onlookers, all pushing and shoving for the best view of the whole wretched ceremony. Eyewitnesses remembered some climbed as high as they could atop wagons to see Henry Harvey die. They grew eerily silent as Sheriff Hinson tied Harvey’s wrists and ankles, then listened for Harvey’s final words.

Henry Harvey disappointed no one, uttering one last, terrifying statement. Standing on the gallows, with death just seconds away, the condemned man spoke directly and clearly: “I want to go to hell for a special purpose,” he said.

The Sheriff pulled a black cap down over Harvey’s face. Next, he adjusted the noose, placing it just underneath Harvey’s left ear, where a perfectly-positioned knot offered the best chance of a broken neck and quick death. But when the moment came for Harvey to die, Sheriff Hinson faltered. He couldn’t bring himself to spring the gallows trap. Instead, he turned to ask a deputy to do that work for him.

At eleven o’clock the morning of Thursday, December 17, the deputy grabbed an axe and, with a swift blow, severed the rope that held the gallows trap in place. Henry Harvey dropped with a thud. Several minutes later, after doctors confirmed Harvey’s death, Sheriff Hinson cut the man’s body down from the scaffolding and placed it in a plain coffin. No one remembers where his body was buried. But evidence suggests his soul descended into hell, just as he wished.

Soon afterwards, the deaths started.

Back from Hell?

Tragedy comes in threes, they say, and that’s the way things tend to play out. As if by dark design, three shocking deaths followed quickly on the heels of Harvey’s execution. Each of the deaths was a blow to the community, and each of the victims played some key part in Henry Harvey’s final days.

Settle Dockery, the man who defended Henry Harvey with all his might, was the first to die.

In the spring of 1911, after recovering from a freak, near-fatal carriage accident, Settle Dockery contracted typhoid fever, a dreadful disease. Typhoid, ironically, was something that Henry Harvey’s sewer pipes and indoor plumbing should have helped to prevent, but didn’t.

Dockery spent three weeks desperately sick, fighting disease and fever, while clinging to life and hope. Then, as the fourth week of sickness began, Dockery developed both pneumonia and jaundice. It proved too much for the man to overcome. He died Tuesday, June 27, 1911. Dockery was just thirty-four.

Henry C. Dockery, father of Settle Dockery, died soon afterwards.

As owner and editor of the Rockingham Post, H.C. Dockery published stories about the murder Henry Harvey committed and the madness that overwhelmed him. Dockery’s Post also carried the news of Harvey’s trial and execution, and his accounts were widely shared by newspapers across the country.

In the fall of 1911, H.C. Dockery contracted severe influenza — la grippe, as they it. He began to recover, only to develop “holy fire,” a severe erysipelas infection from a tiny scratch on his head. Stomach and heart trouble followed, resulting in his death Monday, November 6th, 1911.

The third and final victim, Sheriff M. L. Hinson, died three months later. Sheriff Hinson had handled the details of Harvey’s execution, but couldn’t bring himself to spring the gallows trap.

At forty-seven, Sheriff Hinson appeared to be in excellent health. He had been sick for a few days in mid-February, but thought nothing of it. By Monday, February 26, 1912, he felt better. After a big meal, he retired for the night.

Soon, the Sheriff awoke with severe chest pains. Doctors rushed to his home to administer heart stimulants, but the medicine was of no use. At four in the morning, after suffering through the night, Sheriff Hinson asked his doctors for an honest medical opinion. They told him there was little, if any, chance for recovery.

Sheriff Hinson quickly made his final arrangements. With just two hours left to live, he called his three executors to his side, dictated his will, and said his final goodbyes. He died just as the sun rose on a Tuesday morning.

What an odd and unfortunate twist of fate, people thought, that the town lost three key leaders so close in time to one another. “It is an extraordinary harvest death has reaped in the town of Rockingham within the past few months,” the Charlotte Evening Chronicle remarked, just after Sheriff Hinson’s body was buried six feet deep in Eastside Cemetery.

It is possible the Charlotte paper missed the point. Perhaps those three deaths were more than a run of bad luck in a small town. After all, a single, evil thread connects them all, and there are clues to help sort it all out.

Most of what Henry Harvey said in his lifetime was quickly forgotten. But his few recorded words were demonic and deeply disturbing. Harvey told his arresting officer, “I want to kill more people.” Standing on the gallows five months later, he declared his desire to go “to hell for a special purpose.”

Henry Harvey knew exactly where he wanted to go and what he wanted to do. If he had to die, maybe he figured a way to end other lives as well. Maybe his “special purpose” in hell was to kill the three local men most closely tied to his execution. If so, he left a shadow across the town, much longer, darker and more enduring than the shadow of the water tower he helped to build.

Epilogue

Henry Harvey had gone to Rockingham to help bring the town into the modern era. He didn’t plan to die there. But if he had to die, maybe Harvey wanted to do more than murder three people from beyond the grave. He might have figured he could bring the entire town down with him.

As he walked to the gallows, Harvey saw a chicken fly over his head and said, “Somebody catch that chicken.” The words seemed nonsensical. But maybe Harvey was not so crazy after all. In the practice of voodoo, the chicken — and particularly the chicken’s foot — holds special power. Normally, a chicken foot is used as an amulet of protection. Some, however, know how to use a chicken’s foot for a more sinister purpose: In parts of the American South, a chicken foot was (and still is) used to place a curse. Could that explain Harvey’s bizarre interest in a chicken in the moments before his certain death?

At the time Henry Harvey was hanged, Rockingham was a town on the move. Many of the town’s projects and accomplishments dwarfed the water and sewer lines Harvey came to construct.

During those years, entrepreneurs built two enormous textile mills, Hannah Pickett and Entwistle. Downtown, the ultra-modern Rockingham Hotel rose over the ashes of the Hotel Richmond. Business owners built twenty new brick stores, two new banks, three livery stables, two garages and a Presbyterian church.

With the population booming, residents constructed twenty-five new homes in 1910 alone. Industry leaders built the eighteen-mile Rockingham Railroad to connect their mills to major lines. Over on the Pee Dee River, engineers and financiers rushed to complete Blewett Falls dam, which promised to electrify the Pee Dee region and beyond.

If it seemed impressive, that’s because it was. “Rockingham is used to doing big things, and making little noise over it,” wrote the Charlotte Evening Chronicle. In 1910, Rockingham spent $272,000 more on industrial expansion than Charlotte. “Rockingham…is destined to be one of North Carolina’s leading towns,” said the Wilmington Morning Star.

Rockingham had just 2,155 citizens in 1910, but the Wilmington paper predicted, “Within the next decade, Rockingham will be a city of more than 20,000 people and it will take a dozen banks to care for her financial interests.“

Nothing could derail Rockingham’s progress, it seemed. But that’s what happened.

Now, it isn’t enough to destroy a town by fire or flood. Strong town leaders can overcome those kinds of setbacks. To completely destroy a town, a person — or demon — would need to kill off all of the progressive leaders. When enough key leaders are dead and gone, there is no one left to pick up the pieces and drive progress steadily ahead.

After Henry Harvey swung from Rockingham’s gallows, the untimely deaths of Settle Dockery, H.C. Dockery, and Sheriff Hinson brought local progress to a halt for many years. The town, which some predicted would be home to 20,000 people by 1920, remains less than half that size nearly a century later. Henry Harvey, the man who wanted to go to hell for a purpose, could be the reason.